.

.

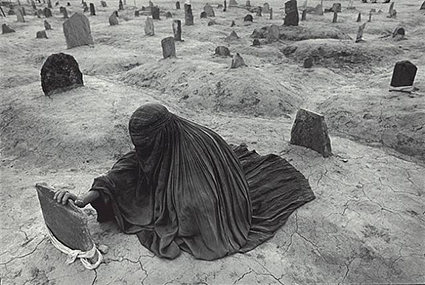

James Nachtwey

View 12 Great Photographs by James Nachtwey

James Nachtwey grew up in Massachusetts and graduated from Dartmouth College where he studied Art History and Political Science. He worked aboard ships in the Merchant Marine and while teaching himself photography, he worked as an apprentice news film editor and a truck driver.

For four years he was a newspaper photographer in New Mexico, and in 1980, he moved to New York to begin a career as a freelance magazine photographer. His first foreign assignment was to cover civil strife in Northern Ireland in 1981 during the IRA hunger strike. Since then, he has devoted himself to documenting wars, conflicts and social issues worldwide. He has worked extensively in El Salvador, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Lebanon, the West Bank and Gaza, Israel, India, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, the Philippines, South Korea, Somalia, Sudan, Brazil, Rwanda, South Africa, Russia, Bosnia, Chechnya, Romania, Viet Nam, and throughout Indonesia and Eastern Europe.

His work has appeared regularly in many of the finest international publications, including Time, Life, New York Times Magazine, Newsweek, National Geographic, Stern, Geo, El Pais, L’Express and many others. He has been a contract photographer with Time since 1984, and a member of Magnum since 1986.

His books include Deeds of War published in 1989 and Inferno published in 1999. He has had one-man exhibitions at the International Center of Photography in New York, the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College, the Carolinum in Prague, the Hasselblad Center in Sweden, the Canon Gallery, the Nisuwe Kirke in Amsterdam, and Massachusetts College of Art, where he was awarded an honorary doctorate.

A Canon Explorer of Light, he has been awarded Magazine Photographer of the Year six times, the Robert Capa Gold Medal four times, the World Press Photo Award twice, the International Center of Photography Infinity Award twice, the Leica Award twice, the Overseas Press Club Award for Best Photo Reporting from Abroad twice, the Canon Photo Essayist Award, the Eugene Smith Memorial Grant, the Bayeaux Award for War Correspondents, the Sprague Award (the highest award given by the National Press Photographers Association), and most recently the 2000 Alfred Eisenstaedt Award for magazine photography for single image–journalistic impact

James NachtweyI think the raising of people’s consciousness is the first step toward creating public opinion and public opinion creates an impetus for change. It creates pressure on decision makers, the powers that be, who make choices that affect the lives of thousands of people. Helping create the impetus for them to move in the right direction, through public opinion, is something worth doing.

In spite of all the frustrations and setbacks, I think it’s a process that works. Sometimes it’s more immediate, sometimes it’s agonizingly slow. But, that pressure always has to be there to drive the process forward. It helps. It’s quite often at odds with what governments are putting out, the information and the spin they want to put on events because essentially they want to rule the agenda. I think they find public opinion annoying. It gets in their way. And indeed it should get in their way. It should help divert them to the right course.

The disaster of U.S. policy in Somalia led directly to our ignoring Rwanda. Our ignoring Rwanda, and knowing that the international community had a degree of accountability for a half million to a million unneeded deaths, led to not accepting what was happening in Kosovo. These things are linked. My book (Inferno) is a record of what happened in the final decade of the 20th century of crimes against humanity that are linked. Sometimes in a very direct way, sometimes in more subtle ways. The book culminates with Kosovo.

John Paul Caponigro Linked in what way?

JN Take the example I gave you of the disaster of U.S. policy in Somalia. The mission began with goodwill and good intentions and was effective. That mission was to protect the distribution of food relief to famine victims. When it turned into a political mission to disarm the militias and then to go after one of the warlords, it changed dramatically and turned into a disaster. That disaster was what prompted Bill Clinton to turn his back on Rwanda. He didn’t want to get burned again in Africa and therefore consciously refused to use the word genocide, because he realized that word carried an obligation to intervene. The United Nations did the same thing. Kofi Annan was in charge of the peacekeeping forces at that time and they pulled out during the genocide rather than going in. Again, that was linked to the disaster in Somalia. It was a public relations disaster. And, as it turned out, so was Rwanda. It was the wrong thing to do, and they understand that they’re accountable in some way for those deaths. They both went to Rwanda and apologized to the people there, which is a very rare thing for any politician to do. They admitted they were wrong and they apologized. And when Kosovo came around, when the Serbs began to ethnically cleanse Kosovo, I think the international community understood it couldn’t turn its back on Kosovo the way it had on Rwanda. There’s a connection there.

JPC You speak of our “collective responsibility” and I was wondering, for those who are uncertain of how to act after seeing your work, what suggestions you might have to offer them.

JN I think on the most basic level, if people are confronted in the press with injustices and crimes against humanity, they should engage themselves with the issues. They should keep it alive inside themselves and not turn away from it. If it’s challenging to understand, they should try and understand it. They should give it the time to think about it so they come to grips with what’s going on and communicate with each other. In that way, a constituency is formed. That’s how public opinion is created and that’s how it stays alive. A step beyond that would be to communicate with someone, an official at the United Nations, an ambassador, someone in the State Department or the government. Send a letter. Let them know, “I know what’s happening there. I think something should be done about it. It’s not acceptable.” I think it’s a matter of allowing yourself to have an opinion and becoming part of a constituency that has an influence. That’s power. In a democracy, it’s composed of many individual voices – together. That’s what it’s made of and that’s what our leaders have to listen to. I think it has an effect.

JPC Does it?

JN Yes. Unless you think that public opinion doesn’t count for anything. I believe that it does. I think it had a lot to do with the United States getting out of Vietnam, much sooner than it would have otherwise. It had an effect on our policy in Central America. It had an effect on famine relief in Ethiopia and in southern Sudan and in Somalia. It had an effect on Kosovo. I think there was tremendous support for the intervention on Kosovo. People understood it was something that was justified.

Again, the initial step is to engage yourself as an individual with what’s happening, to keep it alive inside yourself, to have an opinion, to let that opinion be known, to people around you, and to people in the decision-making sphere.

To remove yourself from that process is really a disservice. There are many kinds of action that are effective. What is not effective is to do nothing. That’s always an option, but what good does it do? In Rwanda a half million to a million people were slaughtered while we did nothing. Is anyone happy about that? I don’t think so.

JPC That is the kind of encouragement I am looking for.

JN There’s also a journalistic responsibility, journalistic publications and broadcasts are responsible to inform people about what’s going on. So much space is given over these days to lifestyle and celebrity, fashion, and domestic political scandals. It’s all become a kind of entertainment, which is certainly one aspect of the press. It is a business. They have to do something which they feel generates income. But there is also something called journalistic responsibility and that requires a certain balance and regard for the intelligence and compassion of the audience. People actually want to know what’s going on.

A lot of the decisions that are made now in journalism are market-driven not journalistic. Even the phrase “compassion fatigue” is somehow related to advertisers more than to the general public. Advertisers don’t want their products displayed next to stories about injustices and destruction and suffering. To call that “compassion fatigue” is a kind of apology for not running those stories. Maybe advertisers have to understand their own larger responsibility. In a free society, perhaps they should encourage those stories rather than discourage them because it’s beneficial to the nation and to the world. That might be too idealistic or naïve. But it is one world we live in.

JPC It is. As consumers we also have to provide support for quality information. Demand can drive supply. So can a lack of demand.

JN I’ve never heard them use the phrase “supermodel fatigue”, for example. I think that there are many people in the general population who feel “supermodel fatigue”, but you don’t hear publications using that phrase.

JPC They’re selling something. Famine victims aren’t.

JN When you publish stories and photographs about people who are suffering, you have to be prepared to give something, and not to sell something. I think people are ready to give something.

JPC How you deal with processing this kind of subject on such a sustained level for such a long time?

JN All I can do is keep going and get deeper into it. There’s no running away from it. There’s no escape. I don’t have any crutches. The only way, for me, is to understand the value of the work and to continue.

JPC How do you maintain your faith in humanity in the face of such inhumanity?

JN The people I encounter when I’m in the field – that’s where my inspiration comes from. To see ordinary people coping with such disasters and such suffering, continuing to go on, surviving, trying to make a life, to maintain their family – it humbles me. I don’t know if I would have their strength and their grace and that inspires me. People deserve better than what they’re getting, and what they’re getting is quite often not necessary. It didn’t have to happen. It’s not the natural condition and something can be done about it. My faith in humanity comes from what I witness it.

JPC It certainly puts things in perspective for me, any suffering I feel I might be going through or difficulty I might be encountering, looks pale, almost inconsequential, in comparison to the suffering of others I see in your photographs.

JN Absolutely. It gives people perspective.

JPC How do you approach the temptation to intervene or become involved in a situation before you?

JN I am involved. Being a witness, offering testimony, is being involved. It’s a choice; an active decision. It’s not passive. It’s a deep commitment. I become involved in a more immediate, hands-on way if necessary. I understand what my function is, but I also recognize that there are certain times when I’m the only one who can actually make a difference in saving someone. When that’s clear to me, I put down my camera and do my best to help. Anyone would do the same thing. Most of the time, for example when I’m photographing someone wounded in battle, they’re already being cared for by their medics or comrades. There’s nothing more I can offer. To meddle with that would only be a way to make myself feel good. As long as I can see there’s nothing more I can do, then I carry out my responsibility in being there with a camera. I’ve seen people being attacked by mobs and I’ve stepped in because I realized that I might be able to save them. Sometimes I’ve succeeded and sometimes I haven’t, but I’ve made the attempt. If I find someone in a famine, who doesn’t know where to go to receive food, who is lost or powerless to move, I will take them to a feeding center. But most of the pictures I make in a famine are in a feeding center, where people are already being cared for, as much as they can be.

JPC Tell me about your “relationship between conscience and art.”

JN I use what I know about the formal elements of photography at the service of the people I’m photographing – not the other way around. I’m not trying to make statements about photography. I’m trying to use photography to make statements about what’s happening in the world. I don’t want my compositions to be self-conscious. I don’t want them to attract attention to themselves. When the viewers look at my pictures, I want the immediate impact to be directly between themselves and the people I’m photographing. I try to use photography, in a very elemental, very basic way. It’s challenging and I think I’m continuing to evolve in my ability to do that. I don’t want to make generic images. I don’t want to make illustrations that have no emotional or moral impact. I want to create a strong sense of identification.

JPC You say that the images that you are creating are both objective and subjective. Help me understand that more clearly.

JN When something is happening in front of my eyes the feelings I have toward it are refracted within me. Whatever I feel about it is a product of my history as an individual. I try to channel those feelings into the pictures so that the viewers are getting my sensibility about the facts of the matter. It can be done. That’s the only way it can be done that’s convincing.

JPC What happens to the objective nature of the work in the process? Is it washed away or are both levels married?

JN The confluence of the objective and the subjective is where it becomes real. I make my communication and where I have things in common with other people is where we share an emotion. I can bring people to a point of view only because they share the emotion. I am amplifying or clarifying something that people feel and they haven’t been able to articulate. Whatever emotions I’m feeling in the situations that I enter into are very powerful emotions. There is a tremendous amount of anger, of sadness, of frustration, of grief, of disbelief. It wouldn’t do any good if I allowed those emotions, strong as they are, to shut me down. Then I’d be useless, I shouldn’t have gone there in the first place. I have to take my emotions and channel them into the work. I hope that, in the end, they express compassion.

JPC It’s a courageous act to look at the material in the first place, but to go back time and time again, I’m not sure if there’s another word for it other than heroic. It’s very difficult to conceive, for many of us, of even approaching the material. Spending that much time with it is an entirely different thing. It’s pretty unusual.

JN It’s not for everybody to do this, I recognize that.

JPC So some of us are glad that there are people like you, out there doing this, knowing that it’s not for us.

JN That’s good to hear.

JPC There are some who criticize a more arty delivery of this kind of material -coffee table books, galleries, museums, fine prints, all art objects. They claim that these kinds of treatments exoticize this material, making it glamorous, at times status oriented, even fetishistic, pushing it toward sensationalism. Conversely others would say that its entrance into these worlds brings greater and more sustained attention to the material. While some would criticize Inferno as one of these arty objects, at the same time, others would claim that as a result finds greater durability and increased importance. How do you feel about this kind of delivery of this kind of material?

JN To me, Inferno is not an art object, it’s an archive. The basis of the design, the size, the whole physical presentation, is to create an archive that will enter into our collective memory and our collective conscience. The primary function of my work is to appear in mass circulation publications during the time that the situations are happening in order to create consciousness and public opinion and to bring about an atmosphere in which change is possible. That is the reason I do it. A secondary function is to enter into our memory so that these things are preserved and not forgotten. They’re a visual legacy to contemplate as we go into the future. Hopefully we won’t make the same mistakes we’ve made in the past. There’s a value in that.

I’ve shown a couple times in museums and that’s also a valid form of communication. The agenda of a museum is not set by critics. It’s not exclusively set by the people who run the museum. It’s also set by the people who attend the museum and by the artists who show there. Because a work hangs on the wall of a museum does not necessarily mean that it’s there to be contemplated purely as an art object. It’s there to communicate very immediately with the viewer, perhaps a particular kind of viewer, perhaps a more circumscribed audience, but nonetheless an audience than in journalism but nonetheless an important audience of people who have important opinions.

Although I haven’t had one, if I were to do a gallery show, I would try to make it another form of communication, with perhaps an even more sharply focused audience. Collectors are important. They have wide-ranging interests and wide-ranging influence and they’re well worth reaching out to. I don’t see that some dogmatic stereotype about the meaning of a picture because it hangs in a gallery should stop me, or anyone else, from trying to make that communication.

JPC Along those same lines, your compositions are beautiful. What’s the function of beauty?

JN Beauty is inherent in life, and oftentimes, it’s inherent in tragedy. It’s nothing that I impose. It’s something that I perceive. I don’t think that in my pictures the beauty overcomes the tragedy. It sometimes envelopes it and makes it more poignant. It makes it more accessible. The paradox of the co-existence of beauty and tragedy has been a theme in art and literature throughout the ages. Photography is no exception. The beauty of a pieta is in the body language, it’s in the connection between the mother and the son. The pieta is not a figment of imagination, it’s taken from life. A photograph that resembles a pieta is not an imitation of art. It’s a representation of the source of that art in real life. The beauty is still in the connection between the mother and the son.

JPC I’m reminded of the word you used, compassion. I think as long as that is present, that ensures that that will happen. It’s one matter to make suffering beautiful. It’s an entirely different matter to recognize the beauty of the sufferer.

You said, “our ability to communicate produces an agonizing awareness which, in turn, demands response.” Tell me more about your statement “a perfection of means, but a confusion of aims, is the misfortune of our times.”

JN At a time when we have the wealth, the infrastructure, and the technology to accomplish so many things, we are often confused about how to direct the tools at our disposal. There was confusion about what to do in the case of Bosnia, for example. That was a war that didn’t have to happen. Once begun, it could have ended much sooner if there had been resolve on the part of world leaders to use the diplomatic and material resources at hand. But, there was confusion and conflict and compromise. Those tools were never properly put to use and the war dragged on years longer than it might have. We had the resources to prevent the genocide in Rwanda, and yet, again, there was confusion and compromise, and the resources that were at our disposal were not used.That’s what I meant.

JPC This highlights how important it is to become clear on what’s happened before and where we are today, so that we can take effective action as new situations arise.

JN Absolutely. As best we can.