The Top 20 Photography Books That Influenced Me

“Enjoy this collection of photographic books that have influenced me during some of my most formative years.

#1

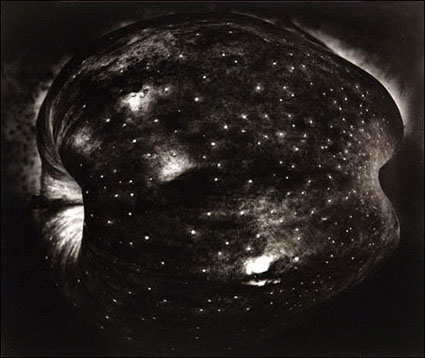

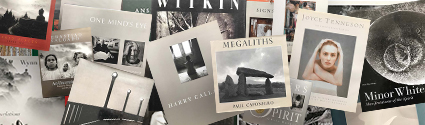

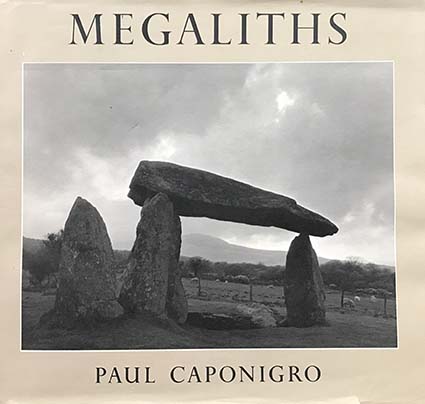

Paul Caponigro – Megaliths

Watching the production of this project from start to finish had a profound effect on me. The book was the culmination of decades of work on so many levels.

#2

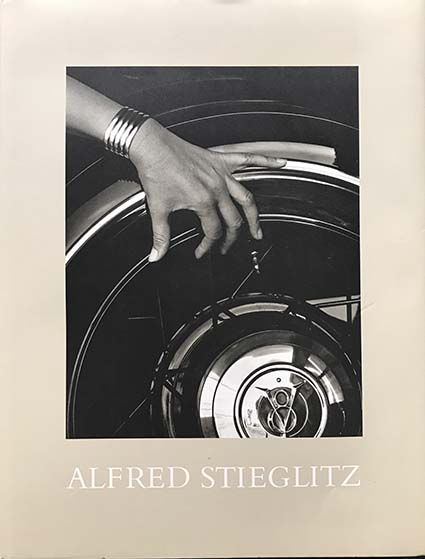

Alfred Stieglitz – Portrait Of Georgia O’Keefe

These portraits and nudes set the highest standards for me. Deep complex emotional connection. The variety of Stieglitz’ printing was eye opening. Meeting O’Keefe was interesting; I still wonder what it was like for her as an older woman to produce a book on her younger self.

#3

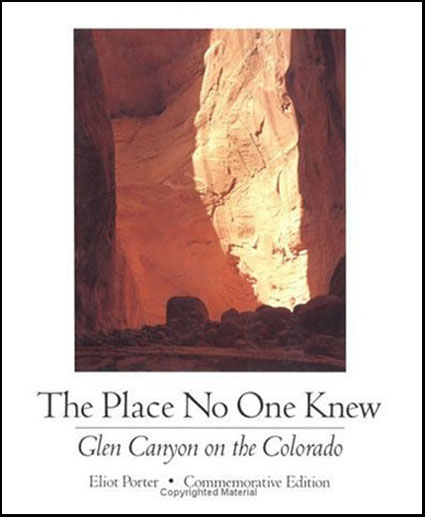

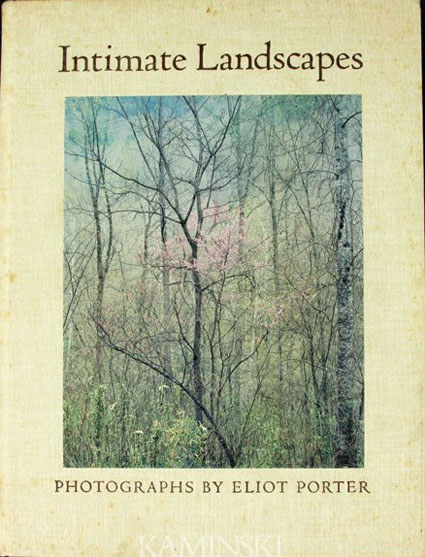

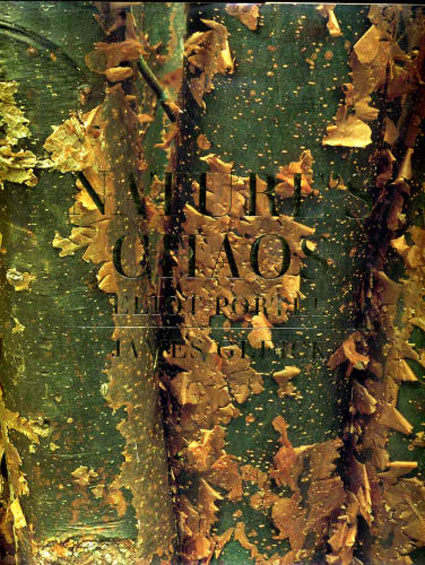

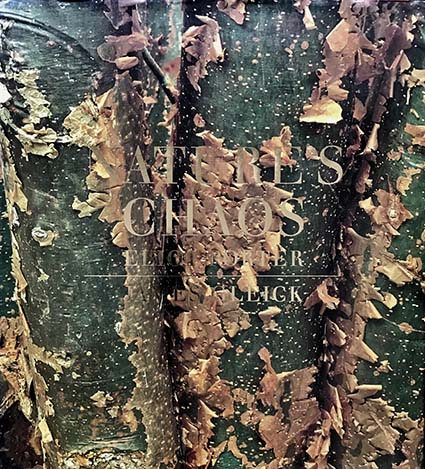

Eliot Porter – Nature’s Chaos

Fortunate to see my mother design many of Porter’s books, this one confirmed my feeling that he saw a deeper order in nature before we more fully understood complexity in the sciences.

#4

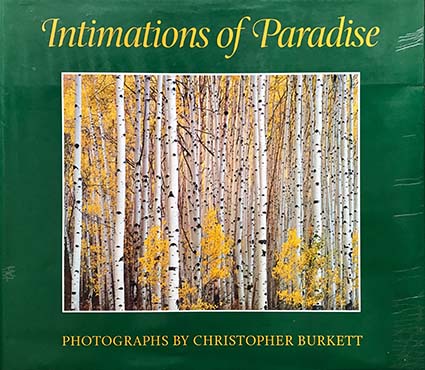

Christopher Burkett – Intimations Of Paradise

Formerly a Gnostic monk, Burkett renounced his vows of poverty so that he could afford film and continue to faithfully transcribe The Book Of Nature. There are so many ways to live life in a sacred way

#5

Edward & Brett Weston – Dune

Dune / Edward Weston And Brett Weston collects works, many never before printed, by father and son showing how similar and how different each artist’s vision was. Working with Kurt Markus to produce this book was eye-opening.

#6

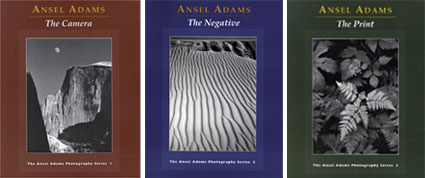

Ansel Adams – The Making Of 40 Photographs

It’s wonderful to read how an artist works and even better to see them in action; I was lucky to do both. I do wish Adams wrote more about why he made each image and what it meant to him.

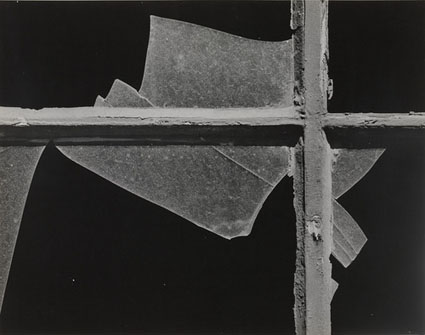

#7

Jerry Uelsmann – Process & Perception

It demonstrates how process changes perception – and the process you engage is a personal choice. The inside is just as important as the outside.

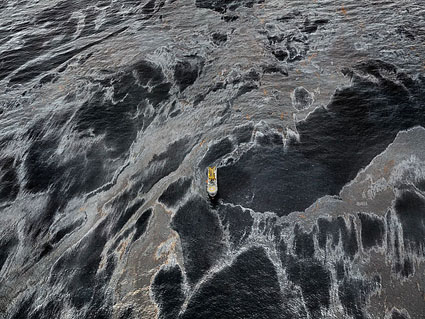

#7

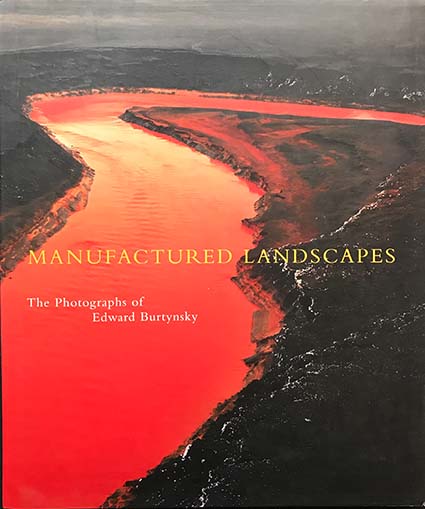

Edward Burtynsky – Manufactured Landscapes

While Eliot Porter didn’t want to beautify trash through art Burtynsky turns an unflinching eye towards industrial impacts on land crafting a complex statement on land use and ultimately identity.

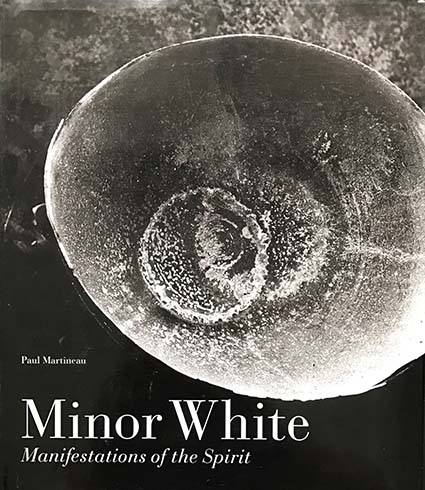

#8

Minor White – Manifestations Of The Spirit

No other photographer is as articulate about the inner experience of making art. His essay on equivalence is seminal.

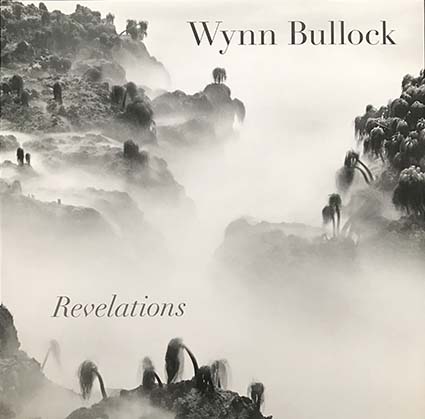

#9

Wynn Bullock – Revelations

Bullock’s marriage of science/physics and art

became as much a philosophical statement as a celebration of beauty.

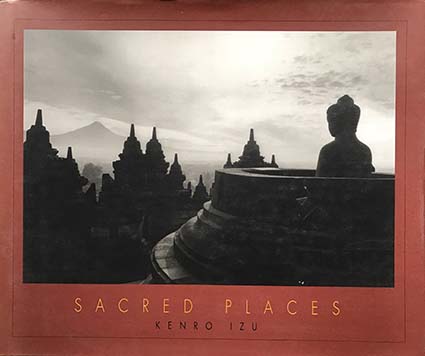

#10

Kenro Izu – Sacred Places

Izu tries to photograph the spirit of ancient sacred places. When he talks about atmosphere he means more than weather.

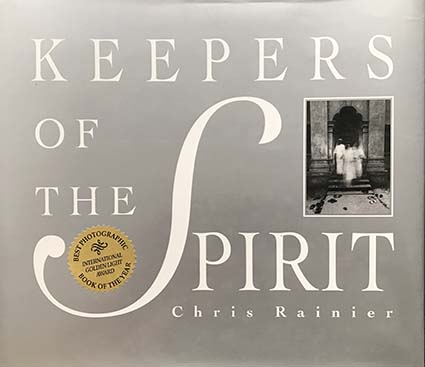

#11

Chris Rainier – Keepers Of The Spirit

If Edward Curtis met Joseph Campbell you’d get Rainier’s survey of spirituality in world cultures.

#12

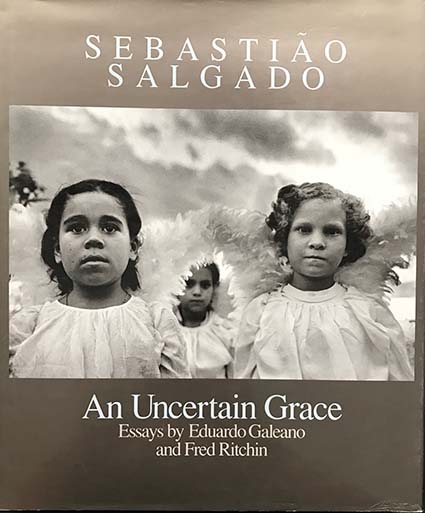

Sebastiao Salgado – An Uncertain Grace

Salgado sets the bar high by bringing out the dignity within his subjects no matter how undignified their circumstances.

#13

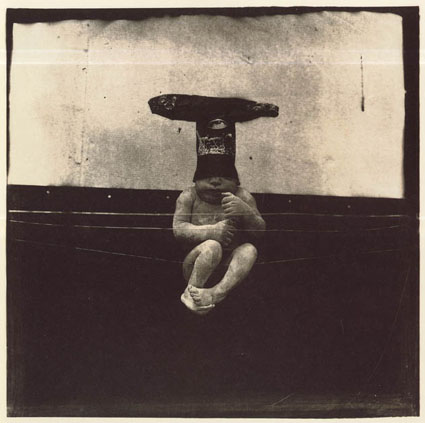

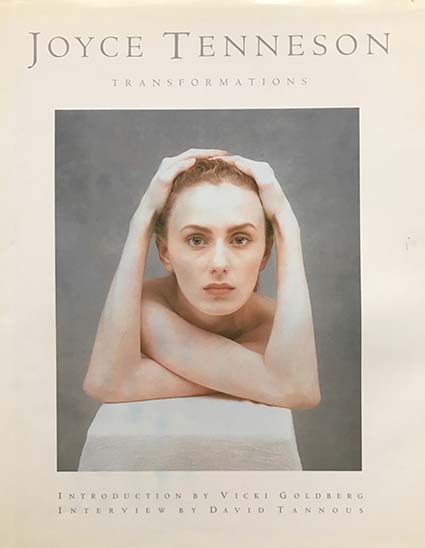

Joyce Tenneson – Transformations

Tenneson’s images remind me of what Pierre Teilhard de Chardin said, “We are not human beings having a spiritual experience; we are spiritual beings having a human experience.”

#14

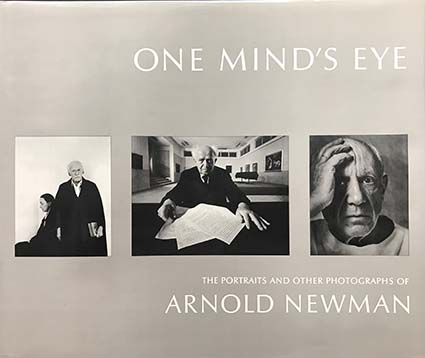

Arnold Newman – One Mind’s Eye

Beautifully constructed portraits from the father of environmental portraiture.

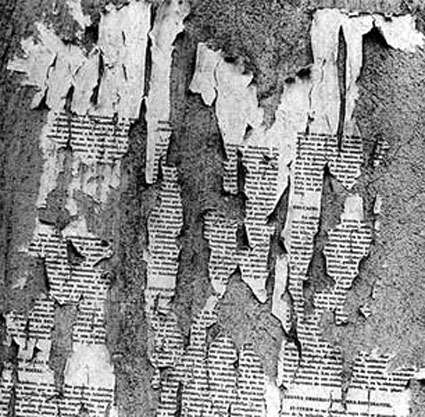

#15

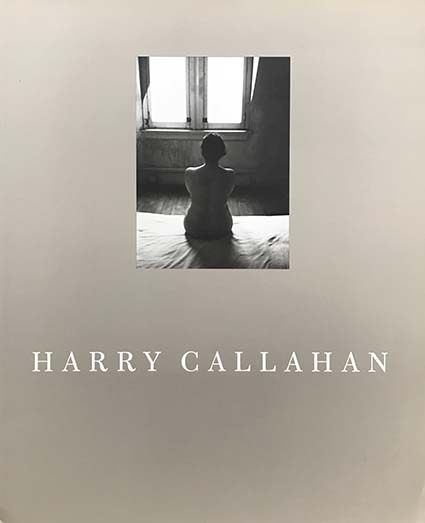

Harry Callahan

The rest of his wrestlessly inventive work intrigued me but his deeply honest extended portrait of his wife set a standard I hope for in all others.

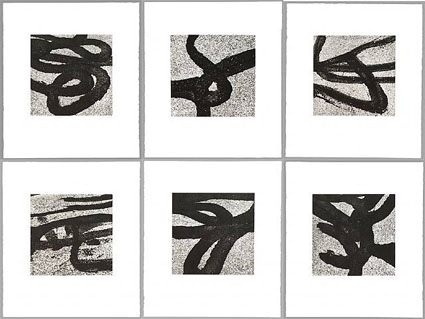

#16

Sugimoto

It’s minimalism that isnt shallow or evasive; the collection reinforces the concept, creating a context for itself. It asks so many questions? Enough? Not enough? Do all the world’s oceans look the same? Or is it just one ocean? Is it the camera or the artist who makes them look the same? Is it the way we look? How is it that by looking at them long enough I begin to see myself?

#17

Richard Misrach – The Sky Book

Pleasant as it is this minimalism ordinarily wouldn’t be enough for me. But then he adds the titles of time and places in many languages with a history. Together they grow stronger and placed within his life work as one of many Desert Cantos they grow stringer still. Rebecca Solnit’s accompanying essay is excellent. I learned a lot from looking at this – about art and myself.

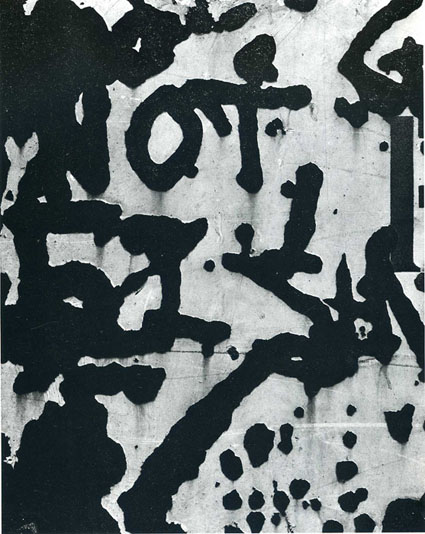

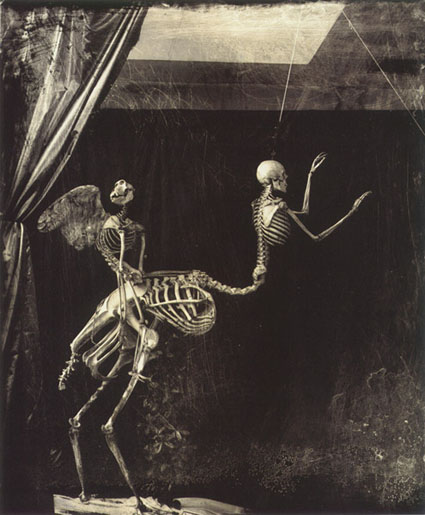

#18

Witkin

I find Joel Peter Witkin’s work profoundly challenging. I can’t say I love it; I can’t say I hate it. I can say it continually crosses back and forth between self-indulgently expressing his individual perversions and courageously looking unflinchingly into a universal heart of darkness.

#19

Michael Kenna – Night Work

Kenna’s elegant minimalism is laced with a quiet spirituality that comes less from tradition and more from being in the moment, growing most emotional when he’s in the dark.

#20

Huntington Witherill – Orchestrating Icons

It’s musical for its flowing compositions and exquisite tonalities. Extraordinary separation in extreme highlights and shadows, no one prints quite like him in.

Find out more about my influences here.