Make Your Inner Critic An Ally

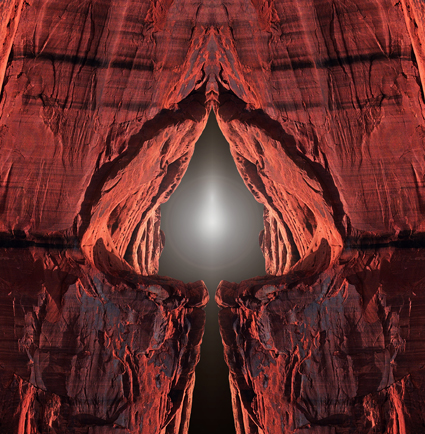

Enchambered, 1996, Arches National Park, Moab, Utah

The symmetry is marvelous, but it would be even better if it was rotated a few degrees. The color is rich, but it could be a little more saturated – not too saturated. The shadows are a touch too dark; they need more detail. The space in the center is too empty. What should go in it? A stone? It blocks the entrance. A bone? It brings unwanted associations of death. A tooth? Don’t give Freud the pleasure. How about something non-material like light? That’s it. But a little irregular. Now the environment needs to reflect the new light source. How light should the surrounding walls become? A little lighter, no that’s too light. And lighten only the central arch so that the source of light appears to be in not in front of the canyon walls. That’s it. Are you sure? I’m sure. Are you really sure? That’s enough. So it went, my dialog with my inner critic as I made this image – Enchambered. My inner critic would have been either maddening or demoralizing if I hadn’t come to trust it so much over the years.

Your inner critic can be a terrible adversary or a powerful ally. Which one it becomes depends on how you relate to and use it. Like any animal, proper care and feeding can work wonders while neglect and abuse can produce monstrous results.

The inner critic’s powers of analysis and forethought are truly exceptional. It’s a protective mechanism. Its job is to help you avoid potential dangers. It’s excellent at identifying weaknesses or shortcomings that if left uncorrected and allowed to continue unchecked may have adverse affects. It can quickly identify potential areas for improvement. It can provide all sorts of extremely valuable feedback.

But, the inner critic has its limitations. The inner critic speaks from a point of fear. It motivates with fear too. It’s a pessimist. It’s often accurate, but never infallible. Because of this, it isn’t good at being supportive, but instead may create doubt and insecurity. Its criticism may not be constructive, if its feedback isn’t placed in a useful context. If it goes too far astray, its affects can produce negative results and even lead to paralysis.

So how can you turn this powerful voice from enemy into ally? It’s all in your attitude. First consider the inner critic a trusted ally – one with limitations. Call on it whenever you need a good dose of tough love. Give it free reign to speak candidly and fully, for a limited time only. Weigh everything it offers appropriately; remember it’s wearing the opposite of rose colored glasses. Whenever you hear the voice of the inner critic unbeckoned, ask if what it has to offer is helpful. If it is, use its feedback to improve your results. If it’s not, calmly acknowledge it. Tell it you value it as an ally both in the past and in the future, and clearly state the reason(s) you’ve decided to make the choice you’re making. Tell it you will continue to consult with it in the future. You might even give it an alternate project to work on. Stay calm; it can feed on negative emotions. Once you’ve made your decision, be firm. Remember, like a child having a tantrum, there may be times it needs to be silenced; give it a time out. It can take a lot of energy to manage your inner critic well, so afterwards (There must be an afterwards; giving the inner critic free reign 24/7 is a recipe for depression.) you may need to take a break or even engage your inner coach to reenergize yourself and return empowered with new perspectives.

The inner critic is most valuable at certain stages in a creative process. The inner critic has little to offer early in the creative process; it’s the kiss of death during brainstorming sessions but it’s very useful afterwards when sifting through the wealth of material that’s produced in them. It becomes increasingly valuable further on in a creative process, particularly at key turning points when evaluating results – identifying and rating strengths and weaknesses, opportunities and threats, and performing cost benefit analyses. Often, towards the end of a creative process, it will provide just the thing you need to pull it all together or help you take it up to the next level.

Questions

When are evaluative questions and statements most useful?

When are evaluative questions and statements not useful?

What is the most beneficial attitude to approach them with?

What’s the most productive way to ask and state them?

When are they energizing?

When are they enervating?

How do you reconcile conflicting results that are sometimes generated?

How long should you stay in this mode?

When should you stop?

Find out more about this image here.

View more related images here.

Read more The Stories Behind The Images here.