.

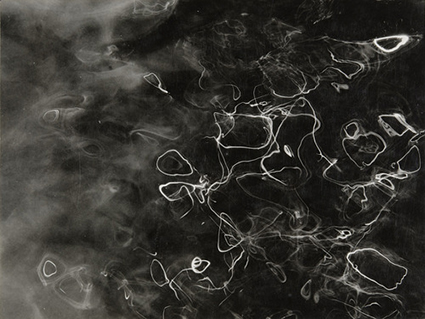

Harry Callahan

Watch the videos.

Born 1912 in Detroit, Michigan Harry Callahan graduated from Michigan State College in 1935, switching his major from chemical engineering to business. In 1936 he married Eleanor Knapp. Lazlo Maholy Nagy hired Callahan as a teacher at the Institute of Design in Chicago in 1946; he became department head three years later. In 1962, he moved on to become the department head at the Rhode Island School of Design. He shaped the photography department there for nearly two decades before retiring from teaching in 1977. He moved to Atlanta, Georgia in 1983.

Callahan was the recipient of numerous awards including a Graham Foundation Award and a Guggenheim Fellowship. Published extensively, his work resides in major public and private collections internationally. In March, at the age of 87, Harry Callahan died, survived by his wife Eleanor and daughter, Barbara. A memorial service was held in Atlanta. Many luminaries from the world of photography attended to say a fond farewell to a dear friend, one of photography’s brightest stars.

This conversation was first seen in the Jun/Jul 1999 issue of Camera Arts magazine.

I had the pleasure of meeting Harry and Eleanor Callahan in the summer of 1997. I was in Atlanta for an opening at Jackson Fine Arts and Jane Jackson kindly arranged for my wife, Alexandra, and I to meet with them. Along with Steiglitz’s portraits of O’Keefe, his portraits of Eleanor had been particularly influential to me. I didn’t know when I would have another opportunity to meet him. He had suffered a stroke some time before. He was weak and had difficulty speaking. During our conversation I started to motion several times to stop, trying to be considerate, but every time I did he seemed to speak faster and louder. It seemed, hard as it was, he didn’t want to stop. I was quietly very impressed by Eleanor; she seemed to have vast reservoirs of charm, grace, patience, and strength.

The night I finished transcribing our conversation I ran into a quote by Lao Tsu. It seemed appropriate.

Therefore the sage goes about doing nothing, teaching no talking.

The ten thousand things rise and fall without cease,

Creating, yet not possessing,

Working, yet not taking credit.

Work is done, then forgotten.

Therefore it lasts forever.

“Photography is an adventure just as life is an adventure. If man wishes to express himself photographically, he must understand, surely to a certain extent, his relationship to life. I am interested in relating the problems that affect me to some set of values that I am trying to discover and establish as being my life. I want to discover and establish them through photography.” Harry Callahan (1946)

JPC I ask everyone in this series, mostly because you get such different answers, how you first go involved in photography and what is it that was particularly interesting to you about photography and photographic vision?

HC I think I valued it. I never studied art or music or architecture or anything like that. I saw my wife’s dentist, he showed me a movie camera. I thought that was beautiful. I thought I would like one. He was excited about the movie camera also. I wanted to get one. I wrote down what I needed but I forgot it. He sold me a Rolleicord instead. I think it was the technology that excited me. I promptly became a photographer. I started photographing at a half second. I thought that was pretty fast – a half second. They were terrible. Slowly I got interested. I had a friend that ran a camera club. I joined. I worked a couple of years. I got a little bit better. I created enlargements. I really got frustrated because I didn’t like what I was doing. I saw Ansel Adams in Detroit. He had almost all contact prints – 4×5, 5×7, 8×10, 11×14. I started making contact prints out of everything; 2 1/4, 9×12 cm Linhof Technica I contact printed everything. I had a friend who traded me my Omega enlarger for an 8×10. Contact prints! Technology really got me excited! With Ansel it was his contact prints that made it technically for me. But I liked his pictures too. Ansel Adams talked about music. He talked about Stieglitz. I had to go see Stieglitz. That’s what he gave me. He had plants. He had mountains. He had western pictures. That wasn’t what did it for me. I thought that nature was a big view. I had been out west and I didn’t really like it that much. I photographed it and I got nothing.

JPC You preferred the eastern landscape?

HC Michigan. Nothing is spectacular. I photographed sand, grass, weeds, anything. I liked that best. I have always been that way. Ansel started me but I didn’t care about the west photographically. I like the simple things. I don’t know why. I’m that way. I came from a simple place. That’s all.

JPC I liked your statement, “A picture is like a prayer.”

HC I was religious about twenty years ago. My friends talked me out of it. I have a religious outlook because of my early days. I can’t say what makes a picture. I can’t say. It’s mysterious. That’s all. I think that we all have our different backgrounds. We’re all different – if we think a little bit.

JPC We all have talents. You said, “You’re an individual and you make something that really comes out of you that is going to be unique.” I think there is a sense these days that one has to be different, to do something that no one else has done before, in order to be unique. I wonder if we place a little too much emphasis on that. I have felt that one finds one’s own uniqueness by discovering what naturally comes from within, rather than manufacturing a unique identity.

HC You only do exercises in art school. That’s not the real thing. A little bit tells you so much. You have to find your own self. And you don’t know what you are! But that’s what you have to search for.

JPC Very often it’s the process of doing the work and the work generated that tells us this.

HCThat’s right. Every time I talked about making a picture I didn’t do it. I had already done it – talking about it! I quit talking. I find in my own way I don’t really know anything that I can talk about. I am not that kind. It’s too mysterious I think. I said to Mies van der Rohe (?) “What do you think is the most important thing?” He said, “Work.” That’s the only thing he knew, really. You have to find your own way by working. In graduate school, at RISD, they all tried to be different. None of them were different. One guy liked Walker Evans very much. He tried to imitate him. He was better, I think, than the rest. He wasn’t trying to be different. It’s crazy. When I first went to RISD they had caps and gowns, all the traditional stuff; when I left sometime later they wore blue jeans with holes in the knees and one or two students during the graduation wore the cap and gown. They were the only ones that were different. I think it’s so hopeless to try to understand but we try.

JPC It’s a worthy struggle.

HC I think so. But I can tell you for me it goes on forever. There are some things you can’t ever find out. You can’t find out in one life either.

JPC There’s not enough time is there?

HC I think there’s no answer!

Just work.

JPC Hmmm!

HC I look at it with hope. Civilization. America. Everybody, not everybody, most everybody, tries to do good. I think that’s what we struggle for in art, religion, what have you. I’m not religious anymore. I’m not anything. That’s one way of living, but that’s not the only way.

JPC I often wonder if the answer we find is simply the experience of our life. Perhaps we find our uniqueness through our unique experiences. Each life has it’s own story.

HC Sometimes when you photograph you think you have something real good and it’s lousy.

JPC Other times things sneak up on you and they’re magnificent. Do you feel that way about many of your photographs?

HC That’s right. I know I have a direction but I only hope something will come out.

JPC So much for previsualization.

HC Yes. Well I think previsualization doesn’t mean anything; technically it means something.

JPC Peter Bunnel wrote something quite nice about your work. “His pictures were all meant as a confession of deep interest and respect. He is truly in love with woman and he lives and breathes this admiration in reverence … Apart from Steiglitz’s obsession with O’Keefe it is doubtful if the woman’s world has ever before been so fully revealed in photographs by a man.” Your portraits of Eleanor over time were particularly honest and direct. They share something rare. I wonder if you felt a certain way about that body of work.

HC I think that’s something different. I don’t know how to say it. She was innocent and I was innocent. I just try to photograph what I like I like I thought she was beautiful. I intuitively photographed her. All my photography is innocent.

I saw, technically, Ansel Adams but I started myself. I have always been that way. I had no training. I think it was lucky. It was for me. I have seen many people at RISD and Chicago. You can see the ones who had training, from their family or school, they’d do real good in the beginning because they had a head start. But the crazy ones do better in the end! You can’t explain anything … and get away with it.

JPC If we could explain everything that was important in our pictures we could just be writers.

HC That’s right. I think you have to have some faith in yourself. You plod along. That’s all.

JPC Someone asked you, “Do you believe you are consciously trying to make the world more interesting.” What a question. How could one possibly make the world more interesting? At the same time when I look at other people’s work it really does make the world more interesting. Do you feel the same way?

HC That’s what I look for.

JPC I wonder if that’s not the same impulse that leads to making your own work. Does photography make the world more interesting to you?

HC I think so.

JPC Peter Bunnel mentioned that a small number of experiences had had a great influence on you. As you look back on your career are there moments you find stand in your mind as being particularly important.

HC I have a dear friend, Don Shapero. He was close to me. He had a masters in writing. He liked photography. I traded my enlarger for his 8×10. He was strong to me. He knew something about art. I didn’t know anything. He was pretty good. I think his teaching was very important. I couldn’t find a job. He took me to Maholy (Nagy). Maholy asked me, “Why did you take this picture?” I didn’t know really. I quickly said, “It was only for a wish.” He hired me then. I didn’t know anything. I photographed. I felt strongly about my pictures, but I didn’t want to talk.

JPC Nonetheless he was able to sense the strength in your work.

HC Yes. He said when we left, “Only once before have I been moved by pictures like that.” I thought he was a good liar.

JPC And you know the true meaning of humility. You had the reputation of being a teacher of few words.

HC I didn’t have much to say.

JPC So often it’s the indescribable things that make the pictures so important.

HC You’re opening a new kind of work. That’s it. Push and bang away. You have to do it to get an opening. Most everyone who does anything has to see his own work. In art school you have to figure out how to get them to work. After they work you have something to talk about. I was nuts about Maholy’s program. What I liked was he was so open. Maholy was everything that was good. He really said what photography was – tone, texture, depth of field. You didn’t talk about a person’s character when you made a portrait. You just took the picture. I didn’t like the stance taken by Stieglitz he was going to shoot O’Keefe but when she appeared he saw everything else. Arthur Seigel gave me the Bauhaus in small ways. Their thinking I like better than Ansel’s. Seigel brought him (Adams) to my place in Chicago. He looked at the pictures. I had camera movement and neon signs. Ansel thought they were ‘no place’. Then I showed him some weeds in stone. Ansel said, “Why don’t you take something real?” Seigel said to him, “They are real. They’re weeds. Stop looking at the pictures with your brain.”

You open the shutter and let the world in. That was about the time Jackson Pollock was painting. Dripping. I think that was part of the time. I felt the same way about my camera movement that I thought Jackson Pollock felt. I think it was part of the time. We had a great wave. Weston, Adams, they were the old guys. Ansel couldn’t take it.

JPC Do you know if he appreciated that work?

HC No. He didn’t. He had a different brain.

JPC I always ask if there is something on your mind that I haven’t asked.

HC I think I came alive when I started photography. Photography is my way of life, that’s all. It doesn’t matter anymore. The director of Atlanta College of Art wants to go photographing with me but I think with the stroke it’s too difficult. My hands don’t really work right. I can’t photograph. Do you know how tantalizing it was? Maybe I have to photograph. I don’t know. I don’t know whether I can go on. I won’t be around very much longer. I’m eighty five.

“I think … I want to express my life, and that’s also true now in my old age. The way I am affected by this fact of my life, I hope that that can come out in my photographs in some way. Maybe not specifically, but how it is affecting me. There are moments when you can put some life in the work, from something in you. And old age is certainly different. I always see people around her jogging and I know if I had to ago a block I don’t think I could do it. All your whole life is different. I just hope that however I’m affected as an old person comes out. So far I still look forward to going out and photographing.” (1994)

I asked several people who were close to Harry to tell me more about him. This is what they shared.

Linda Connor “We used to take field trips with the students from RISD up to Rochester to go visit the Eastman House. After looking at prints all day we’d repair to whatever motel we were staying in. There’d always be a bottle of something in Harry’s room and we’d all be gathered around him. Emmet Gowin would be there and John McWilliams would be there. Harold Jones who was working at the Eastman House was there one time. Everyone had had maybe a bit too much to drink and Harold asked Harry in a maudlin kind of way, “Harry how do you become a great photographer?” And Harry thought for a moment and said, “We’ll you just have to be like Beethoven.” End of story. That ties into the other story. It took me time to understand what a purist he was in terms of elemental things. He used to play down his intelligence. He was not an intellectual. He never really believed in talking very much. It was not his medium. I’m sure when he answered that question he wasn’t being flip he was thinking about the power in the music. There’s a term he’d use when looking at your work as a student. He’d sometimes tap approvingly at something. You could tell he liked it. And he’s say, “Now that’s a dumb photograph. But …” I remember that term – dumb. He’d use it fairly often. It was only recently that it dawned on me, I think what he meant was that it was such a visual thing that it was speechless. At least that’s my new interpretation.”

Bill Burke “His pictures could speak for some human condition in a way that I had never seen other people’s nature pictures working. His photographs made me aware of it. That was his genius.”

Peter MacGill “Harry was very much committed to making color photographs. 1978 is when he decided to work exclusively in color and he worked until 1990 only in color, then he started making some pictures in black and white again. He was traveling to his favorite places in the world to make these pictures. In 1980 he took a trip to Mexico. We called each other senor. I said, “Senor how did it go?” He said, “Well, not real good.” I said, “Why?” He said, “Well, I’m just not happy with what I got.” I said, “Harry you can say that but chances are what you got is really good we just need to look at it together to decide which get printed as dye transfers.” He said, “Oh no, no, no. Don’t worry. I’ll photograph my way out of this.” I was trying to reassure him, he ended up reassuring me. His way of dealing with the problem was to ‘photograph his way out’. That’s Harry.”

Peter Bunnell “That catalog (38th Venice Biennial) came about because of this persistent impression that he of course did everything to foster that he had nothing to say either about his own work or anything else for that matter. I felt having done a bit of research that that was really a kind of pose which many photographers are inclined to take. I decided to call him at his own card, which was to go back through the literature very carefully from the very beginning, to bring to light that he had made some quite extraordinary comments on his own work. He was very cognizant of what he was doing and he had in fact expressed verbal opinions on it or verbal ideas. That’s the genesis of that catalog it really could be called Harry Speaks. Obviously he was close to Emmet and at one point he agreed to speak and show his slides in the auditorium. He got up and he prefaced his remarks by immediately saying, ‘I have nothing to say. I don’t know what all these pictures are about. And I don’t know why you invited me. But since I’m here and I brought some slides lets just show some slides.’ Whereupon he pushed the button and at each critical juncture he articulated the most extraordinary observations about what was going on in his mind and what the pictures represented to him, how he saw the pictures in relationship to other photographers works. And of course the students were completely bowled over because they had swallowed hook line and sinker that notion that Harry was the great mum person.

(86 last paragraph) He had this image that he fostered and projected; that he had little to say, that it was all intuitive, a moment’s thing, and that after he got it down he couldn’t figure out what it all meant and where it all sat. Given the opportunity he would then come forth with marvelous comments. He wrote and expressed things that are the equivalent of several other photographers who made no pretense that they had nothing to say. There’s a kind of twist there that’s very interesting.”

Keith Davis “People cared deeply about Harry and his pictures, even people who never met him cared deeply because of the impact of the photographs. There’s something very profound and deeply moving about the integrity of Harry’s work, the passion he brought to photography. He felt that picture making was something really important to him as a unique human being but also to modern culture. He made pictures that were important to him but part of what his work is all about is the attempt to communicate. It’s about the use of photography to communicate one’s deepest thoughts and ideas to some public out there. Photography in that sense is a profoundly important language that bridges that gap between isolated people and humankind. Harry was not terribly verbal which makes it all the more clear that photography was the way he had to discover who he was, his place in the world, and to try and bridge the gap between himself and other people.

There’s no one in this century that did more to invent or reinvent photographic vision. There are so many aspects of photographic vision that Harry not only explored but explored in depth. It’s really rather astonishing. To see how brilliantly, how exhaustively he explored the many aspects of camera vision. Callahan explored the possibilities of this medium in ways that we still haven’t fully understood. He was profoundly humble, I think because he understood how big a thing the world is, what an overwhelming task it is to begin to make sense of the world. He did make sense of the world through the camera. The work, himself, him as a teacher have all been profoundly influential on several generations of photographers. He was an absolute giant, someone who I admired enormously and was very fond of.”

Arno Minkinnen “The few things he would say were so on target. He was the type of teacher that let you know you were special, who let you know if you believe in something you’re probably going to get it. That’s the way he was. This idea that we find our way of living and out of that our way of working can come about, so that we’re at harmony and peace. If they’re antagonistic to one another we either get divorced or become unhappy, something changes, or we change the pictures to fit the lifestyle and then the pictures don’t really work out. There can be a harmony between the way you live and the way you work, that’s the big lesson Harry taught.”

Jim Dow In the last couple of years I was at RISD Harry started to get well known and he started to make some money on his photography. In my last semester of graduate school he had gotten a grant to go off to France. So he said to us, “Look I want to have this last class with you guys because I’m not going to see you next semester so we’ll have a nice last class.” Well wouldn’t you know it Minor White calls up and says to Harry, “You know we’d always talked about getting our students together. I really want to do a class together.” Harry just couldn’t say no. The last class we had at Harry’s house as we always did. Minor White shows up with all of his students and sits in the corner with his legs folded and Harry’s response to this was to drink a little more than usual and get a little more rowdy than usual. Minor says, “Here’s what we’re going to do. First your students show their work to me and then my students will show their pictures to you.” Which meant that Harry would be sitting for the first part of the evening. Wouldn’t you know I was the first student. Minor White says, “Looks like you took all these pictures at the same time of day. If you were my student I would give you a lighting assignment so you could learn to do different things in different circumstances.” Harry was fuming in the corner jumps up and says, “Well he’s not your student and I wouldn’t.” He walks across the room and says, “Listen I’ve given you a hard time while you were here. I just want to acknowledge in front of everybody that you really did okay. I think you’re terrific.” He clapped me on the back and sat down again. Completely out of the blue, that was the way he often operated. Something would be on his mind. He’d be working on it almost like a dog chewing a bone and then he’d just spit it out. What he spit out was always spot on. He saw people, he saw what they needed, and he did something about it because he really cared about them. It was simply presented but it wasn’t simple. Much later he said to me, “I really follow what you guys do. I’m really proud of what you’ve done.” He was absolutely open. He really did make it clear that he felt we were different creatures and that he wanted to learn from us. He was interested in people. He was really interested in people who were different than he was. He never ever tried to make us in his mold. The people he was most interested in were the people he gave the hardest time because he was trying to get inside what made them tick. Harry really wanted people who would put up a different view.

When I was first in the photo program he had a fire sale. He was going to take a sabbatical. He invited people up. People could look through his prints at a very cheap price. He was selling them primarily to students and friends. It was an in house thing. People went up there and they’d say, “You know that picture, well there’s twenty of them, there’s fifty of them.” For every single picture we knew there were many variants that were just as wonderful. You can’t go though his boxes because you can’t make a choice. The depth of what he did is astounding.