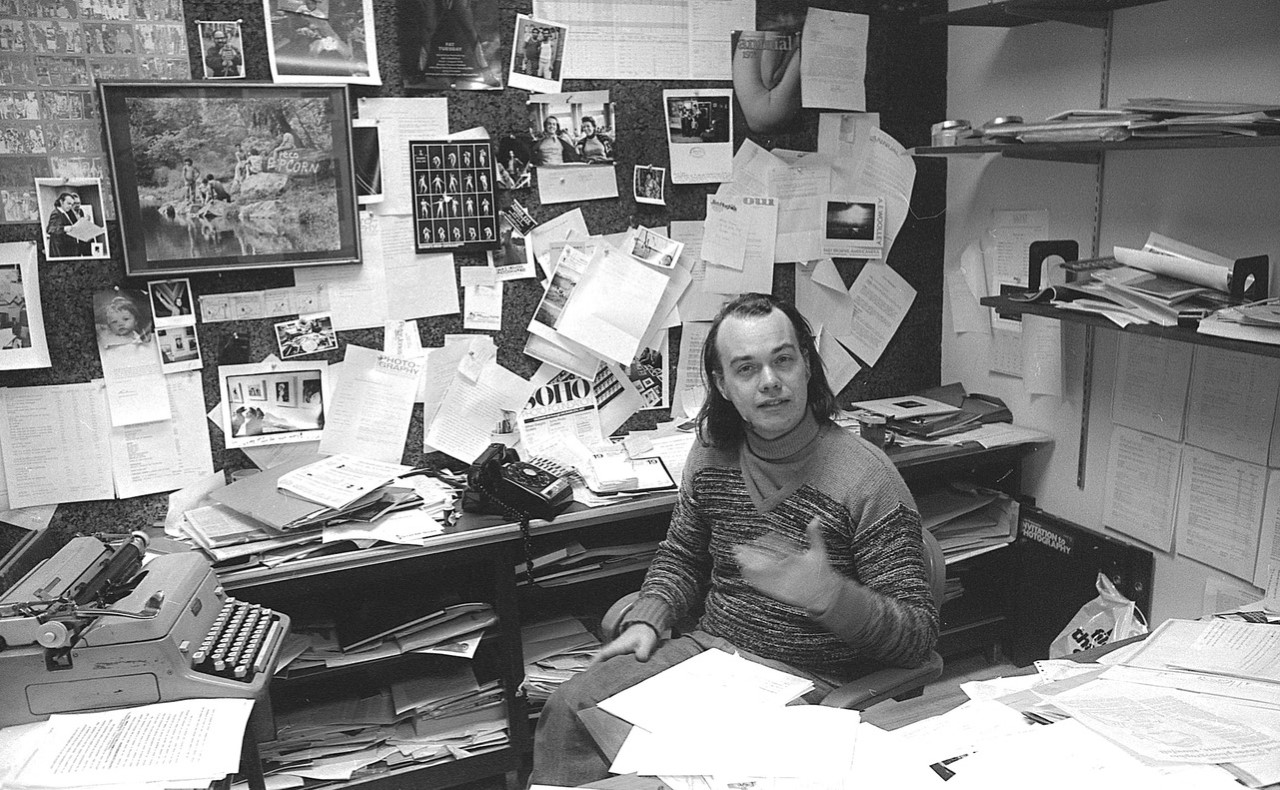

photograph by David Lymann

.

Jim Hughes

Jim Hughes began writing stories and taking photographs as far back as grade school. He attended the University of Connecticut, where he majored in English, History, and Philosophy. After a stint as a reporter/photographer for a daily newspaper, Hughes moved to New York in 1962 to start a new life as a playwright. When reality set in, he began working for various trade journals, Where he learned the craft of magazine editing.

He became editor of Camera 35 in 1967. 1n 1974 he published W. Eugene Smith’s ”Minamata” essay. The magazine won for Smith and his wife, Aileen, a number of awards and ultimately led to the publication of their landmark book, Minamata. When Camera 35 was sold the following year, Hughes became editor of the Popular Photography Annual.

In 1980 Hughes conceived and edited the critically acclaimed magazine Camera Arts, which in 1982 became the first photography magazine to receive the National Magazine Award for General Excellence. He was named Editor of the Year by the National Press Photographers Association in 1983, the same year his publishers decided that maintaining such a high standard of quality was too expensive to support and folded the magazine, selling its subscription list to a competitor.

With the assistance of his wife, Evelyn, Hughes had already begun re-searching the life and work of Eugene Smith. W. Eugene Smith: Shadow & Substance, twelve years in the making, was Published in 1989. Other books by Hughes include Ernst Haas in Black and White (Bulfinch, 1992) and The Birth of a Century – early color photochroms of America (St Martin’s Press, 1994).

Hughes presently writes a column, “The Long View,” for the newly reincarnated Camera Arts, and is working for both a memoir and a collection of his essays and profiles written over the course of three decades observing the art and craft of photography. He has recently begun printing a selection from 30 Years of his own color photography.

John Paul Caponigro Camera 35 was a little before my time. I gather it wasn’t the typical camera magazine

Jim Hughes We published Larry Clark’s Tulsa before it was a book. We published Ralph Gibson as he was putting together The Somnambulist, his first book. Sometimes we were controversial, sometimes not. We continued to do how-to and equipment stuff, but the significant accomplishment was to publish dozens of photographers before they were known at all and I continued and expanded on that philosophy later, in the original Camera Arts. Hooking back, I think the most important refinement I brought to photo magazines was the creation of substantial communal space, where readers could engage in a kind of give-and-take with and about pictures.

JPC Now is it only photographers who are interested in that? Why is there such a dearth of that kind of thing?

JH Well maybe the fact that most of the magazines I’ve edited ultimately died might tell you a little. I mean, structuring a photographic magazine around the art of photography may not be a great idea commercially. Yes, it’s good for photography. It’s what interests serious photographers. It’s not necessarily what interests advertisers. There is little argument that the original Camera Arts died because advertising was shrinking.

JPC Another example of how commerce determines culture.

JH It was really distressing. It was distressing to me personally because Camera Arts embodied what I believed a quality magazine could be. I viewed it as a kind of New Yorker for photographic publishing. I wanted it to do somewhat the same thing, to bring together readers who become a community and then service them as a community to create a dialogue so that through pictures, through letters, through the articles, they could all be talking to each other. I felt I had achieved something I lad long wanted to achieve. I’d been in magazine publishing for a long time and had many starts and fits. Twenty years at that point. The thing I do best is magazine editing and here I had lost magazine editing. There was no other vehicle I could edit and be proud of and I wasn’t going to go back into something less good. So I just stopped, stopped and went to a new career basically.

JPC That’s what your biography of Gene Smith, Shadow & Substance, represents then, a sea change in your own life. Did you have an overriding purpose in mind when you started the book?

JH To get inside his skin, to understand the enigma he had become.

JPC Well I think you certainly did. The depth it goes into is extraordinary.

JH Unfortunately at times I think I was close to becoming him. And he was not a great person to become because he was so full of … well it wasn’t anger, it was obsessive energy. He was obsessed with being perfect. I think that’s why it took twelve years to do the book. The first draft was 2,000 pages, typewritten, plus 400 pages of single spaced notes. So I took a lot out in order to get to the 600 pages that were finally published. I bled every time I deleted another slice of Smith’s life. But it was either that or not get it published. I wanted a two-volume set. I couldn’t find a publisher who would do anything but laugh at the idea. Gene Smith just wasn’t enough of a household name.

JPC I see you’re carrying an old rangefinder Retina. But what’s that on top?

JH This is a Leitz auxiliary 50mm finder with a 1:1 bright frame. Now 1:1 means it’s life size. When you look through it you can keep both eyes open. Most viewfinders today are Smaller than life-size, so you can’t use both eyes. With the new Leicas you can’t do that. No SLR I know about allows you to do it. The designers think they come close, but they don’t. This kind of viewfinder will allow you to do it. It projects the bright frame finder into your mind. So once you get used to it, it’s in there, you can see it with both eyes. No more squinting!

JPC It doesn’t get in the way of your left or right eye, whichever you happen to use, and the border of the picture is essentially where the two eyes overlap.

JH Yes. It’s very accurate. If it’s Leitz it’s accurate. Cartier-Bresson used a small Leica and a 50mm lens for most of his classic work. With the eye that’s away from the viewfinder he could see beyond the frame. That allows you to work the picture out as it’s happening. If you look at Cartier-Bresson’s photographs, if you look at his contact sheets, You’ll see that’s part of the secret of his decisive moment.

JPC Did he bracket that decisive moment?

JH Well, there may be a frame or two before or after, but not many.

JPC You’re saying the technology is actually allowing a different perceptual mode.

JH All photographers work within a given technology, and come to terms with the limitations as well as the possibilities. He worked it out.

JPC He could see it coming.

JH And see it going.

JPC You can’t do that under a dark cloth.

JH No. You cannot do it with a view camera, but that’s an entirely different kind of photography. Deliberative. Studied. But if you’re taking slices from the flow of life, you need equipment that is as unobtrusive and as much a part of your eye as possible.

Garry Winogrand photographed in somewhat the same way. I’ve seen him photograph on a couple of occasions. I once ran into him on Main Street in Camden, Maine. He was there bobbing and weaving, letting people flow around him. It was amazing, he was like a boxer. And people never seemed to notice him. They just didn’t see that he was standing there with his Leica, photographing them. They just walked around him, didn’t pay any attention to him, and he was not such a small man. He just had a way of getting invisible. You could see him moving like this, slowly, nothing sudden, the camera to his eye.

I got to watch Gene Smith photographing, as well. I wasn’t really thinking about a book when I knew him but I was thinking that here was a man that I wanted to understand because he was such a genius. He didn’t, obviously do it the same way that Cartier-Bresson did it. He was more like a dancer; he had movements like a ballet dancer. He’d just follow, follow, follow the energy of the people he was photographing. It was very interesting to watch him do it. But you wouldn’t call a man with five cameras clanging off him unobtrusive. He wasn’t afraid to announce himself. Still, people accepted his presence and went on about heir lives.

JPC How does this viewfinder you’re speaking of so fondly inform your own work?

JH Well, the viewfinder just helps me see with greater clarity and precision. The important thing is how small the Retina becomes when folded. I try to carry a camera whenever possible, but I don’t go looking for photographs. I never do that, except when I see one and for some reason miss it – maybe I forgot the camera, or perhaps the light is wrong. Then I might go back. Normally, I just have a camera with me at all times and make pictures that are entries in an ongoing journal of what I’ve seen. I don’t do Cartier-Bressons or Gene Smiths. I do have a different body of Work that’s full of people, but this one that I’m printing now, the thrust of it is that I am trying to understand color and it’s role in my life – color itself. The impulses for photography are pretty complex despite what a lot of people think.

JPC And quite varied.

JH But you have to understand that I’m a little colorblind.

JPC A specific kind of color blind or the typical red-green?

JH Blue-green mostly. I can get up in the morning and put on one green sock and one blue sock and not know the difference.

JPC Really? And yet you’re interested in making color images? Interesting. Albert Pinkham Ryder was colorblind.

JH It’s not drastic but it probably goes a long way toward explaining my interest in these pictures. For example, they favor primary colors. I can see color but I have to really work at it. That’s part of the photographic process for me, seeing the world more clearly by using the camera, working on it.

JPC Do you feel you can communicate what you’re seeing to the viewer even though you know that you’re seeing it differently than the majority of the viewers?

JH I guess I am seeing it differently but all I’m doing is making a picture and a picture is not a reality. To me photography is illusion and always has been. People who think that they’re looking at reality are simply misguided. They just don’t understand.

JPC And this coming from a photojournalist.

JH Yes. But I’d say this about photojournalism, too. It’s all illusion. If you’re out to make a picture and the picture is a separate object from the reality that you may think you’re recording and you actually believe you’re recording reality, then in my opinion you’re using delusion to make an illusion.

JPC It’s not all made up. On some level, something about reality is informing the process of photography.

JH Well of course it is.

JPC There is a spectrum of possible interpretations, a photograph is not raw data. A bias has been imparted to the data, making it information. You have a particular bias and the choices that you make and choose to share with us are specific ones. Ones that maybe as interesting to us as they are to you. Mr. Wittgenstein, how red is red? Do you feel that the red that you are experiencing and wish to communicate to the viewer is really carried across to someone with a different visual set up?

JH The red is what l say it is. And that’s all it is. Because I’m in control of it as the creator of this particular work. That’s all, that’s all. It’s just my red. What I’m saying is, “Here, I’m giving my red to you.” This is how that red affected this other object that I’m using it to describe, within my visual parameters, but it’s not the red that was there. Although it may be close, it’s not the red that was there. It’s a photographic red – an interpretation, a translation. It’s in my mind first, and then it’s on a particular film or paper. My red may become your red, but it’s never THE red. This is just a very small part of why I photograph these kinds of things and why they interest me.

It’s just as important to say that what I’m photographing, generally, is city life, for the most part without people. The artifacts of their existence, what they leave for us to look at… I suppose I’m studying the patterns of so-called civilized life. So that’s also what these photographs are about. That’s what draws me to the subject matter in the first place and another reason I carry a camera.

This stack of color prints represents 30 years. The first picture is that Volkswagen, 1968, Cologne, Germany, Photokina. That’s pretty much when I got serious about color Photography. I had seen some photographs by Ernst Haas, and saw the potential color had for me. I lad been doing black and white before that and I still did a little black and white after that.

For years now, I’ve photographed exclusively in color. Kodachrome. I don’t regret that I left black and white because I’m personally much more comfortable with color even though I’m a greater appreciator of the black-and-white photography of others. Which is, I imagine a conflict in some people’s minds, that I’m so focused on black and white as an editor and as a photojournalistic commentator.

In terms of photographing events and people I think black-and-white is the more useful medium and the more powerful. Because it’s more abstract, it requires the viewer to interpret the photograph. I think that what happens often is that the viewer adds color subliminally to a black-and-white photograph and reads it that way even if they don’t know they’re doing it. I think it makes them pay more attention. Color is easier to look at and easier to forget, I’m afraid. Black-and-white seems to stay with people longer. It has more depth in their minds because it’s not what they would normally see. I wrote a column about this a couple of months ago.

I suppose if I had to name any one photographer who influenced my work, it would have to be Haas. I don’t photograph the way he did, but his work pointed me in the direction of the potential of color photography. Of course, I might have come to it on my own.

JPC Influence can be a tricky thing to talk about.

JH I don’t know how important it is in photography. I think it’s becoming more important in photography now, especially at the universities. Back in Smith’s day you got a camera, on went out and photographed, and you didn’t look at other people’s work. Basically that’s how I learned. I wasn’t aware of other people’s work. I just found this camera, and it was such a wonderful experience, and I just kept going at it, and it gave me a sense of identity that I didn’t have before.

JPC Less work had been done and there was less history so you were a little freer to work? Now it’s a little bit different, isn’t it?

JH A lot of photography today is about photography. And that’s a problem to me. It takes away the joy of photography, the joy of seeing. It takes away this reaction we were talking about, this instant, this wonderful …

JPC … purity, directness, first hand experience?

JH That I think is what’s lost when one analyzes it to death. I don’t think there’s anything dishonest about so-called post-modern work; I just think it’s loony. It’s like listening to one-line jokes. You can only hear so many of them and then they begin repeating themselves. That’s what a lot of photography is today; it gets narrower and narrower and it folds in on itself. Whereas I think the real power of photography is expanding vision or expanding one’s self, Opening to what’s out there as opposed to focusing only within, or having one thought hermetically sealed forever within you and pounding on it over and over again. I think the other approach is healthier … and less boring.

JPC Well it does sustain more attention over a longer period of time. Craig Stevens likes to talk about the enigmatic quality of images.

JH Well I do too. I agree with that totally.

JPC If the image is left open, full of mystery, there’s something left to come back to again and again and again. The image is not a solved equation. There are questions for the artist as much as the viewer.

JH Minor White said, “I don’t photograph for what a thing is, I photograph for what else it may be.” That’s a paraphrase but it’s pretty close. That says an awful lot about photography’s power. He understood it.

JPC You’ve been interested in history for a long time. How has that influenced your work personally?

JH Not very much – at least hope it hasn’t.

JPC With your background I would think it would be a great effort of will for it not to.

JH I think that it probably has been. I stopped photographing at one point for several years because 1 was saturated with photography and other people’s pictures. I was no longer as free as I wanted to be in my own photography. I was seeing other people’s pictures. So I stopped. It took a while to get back into it.

JPC This is the opposite side of an argument some people make, which says that you need to photograph every day. There’s a benefit to backing off, isn’t there?

JH Yes. I think so. I’ve always photographed because it’s a joyful experience. The act of photographing is something beautiful and pleasurable. That’s why I do it.

JPC An affirmative act?

JH Yes. Very affirmative.

JPC Do you write for the same reasons you photograph?

JH Writing and photographing are different functions. And since I do both and not many do, as you know – Wright Morris comes to mind – I may have a different perspective of it.

JPC How do you feel they’re different and when do you feel they complement each other?

JH Well, I don’t know that they do complement each other, I don’t know that they do. But I know that they’re different. I can only refer to my own experience. Writing is a reflective, contemplative process. You get alone with yourself and you try to get into your mind and think things through.

The unconscious plays an important role. When I come to a point in my writing where I hit a wall, my solution often is to just stop and go to bed, go to sleep. I’ll wake up the next morning, go right to the computer, and just let it go. My mind at rest will have processed the information I was trying to deal with and solved the problem for me.

Photography, on the other hand – at least my kind of photography – is not reflective, although in an odd way it may be a little reflexive. It’s a response. It’s a reaction. I see something that triggers something else in my mind. I never need to sleep on it. I don’t have to think about it. It is a physical act. It’s an act of seeing and reacting. I see a picture that matches what l think a picture is. I have certain concepts about pictures and composition and how things work and how images are structured and I bring that to any picture I take. It’s just there. I don’t go in and work it out. I have a sense of what aesthetically falls together and I move myself around until it does or I walk away.

Although I’m a writer I don’t keep a journal. So I guess I can regard this work as my journal. I don’t refer to my pictures as notes, however. They are meant to be complete works when they are finished, if they work out, and they don’t always work out.

JPC You’re someone who has spent a lot of time verbalizing pictures, either writing about them or talking about them or hearing other people talk about their work…

JH You think so? I should let you ask your question first but I’m going to interrupt you anyway. I don’t think photographs can be verbalized very easily, or very effectively. I think a lot of it is unnecessary critical jargon created by people who need to make work for themselves. A lot of it is written by people at the university levels who are justifying their existence, and it goes a little bit too far. Obviously a picture can speak for itself. Some amount of reinterpretation is useful, but it gets to a point where you can kill the picture by thinking and talking about it too much, as you can do with a lot of acts that we do in our lives if they become unnatural or strained. I would much prefer not to talk about photographs and I try not to. What I talk about, what I write about mostly, and you’re doing the same thing, is the lives of the photographers who make the photographs. I think that’s much more important to understand anyway. It’s pretty easy to say that work needs to stand by itself. And it should. But I think it also helps to understand the structure on which the photographs are built. That’s what a life does. I think photography is one of the few arts that comes out of a life being lived. That’s what my pictures are. I’m living my life and I have a camera and I put it to my eye once in a while.