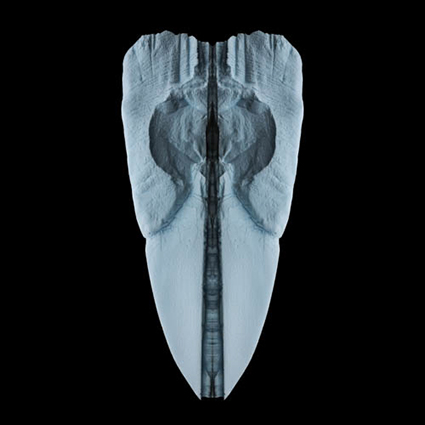

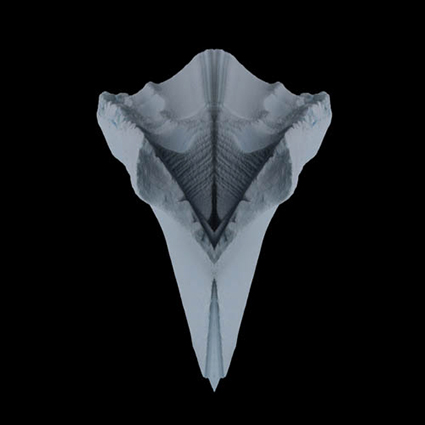

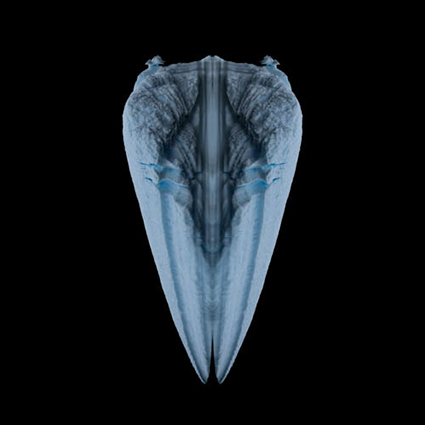

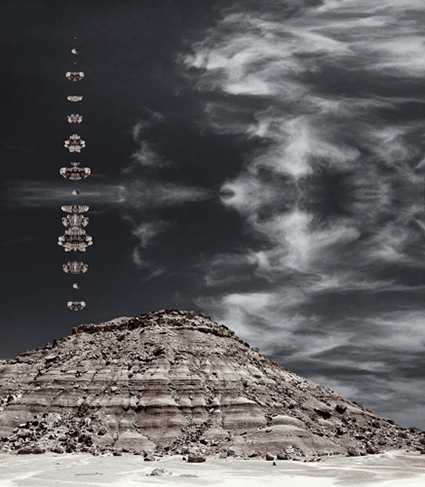

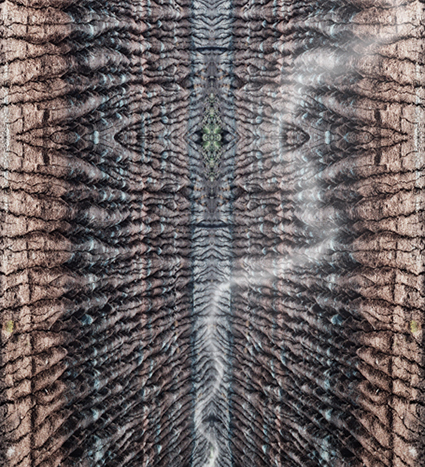

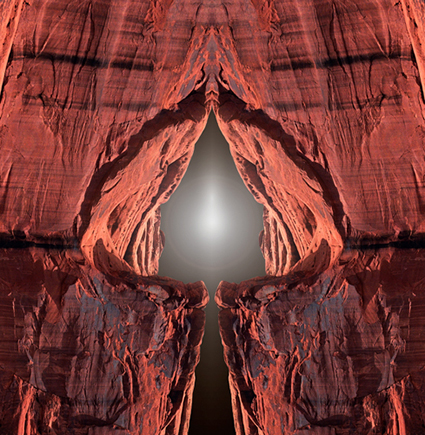

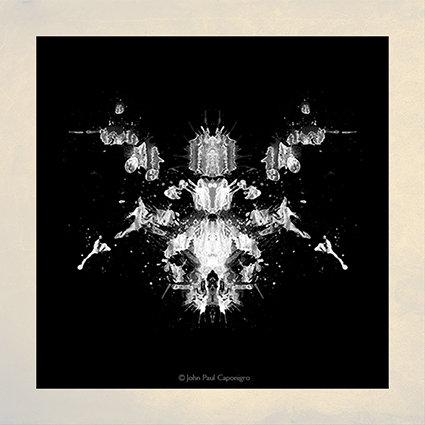

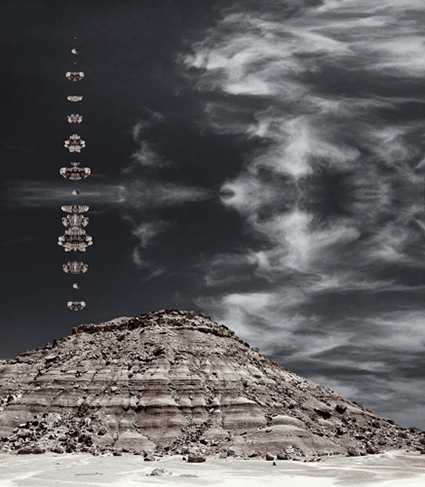

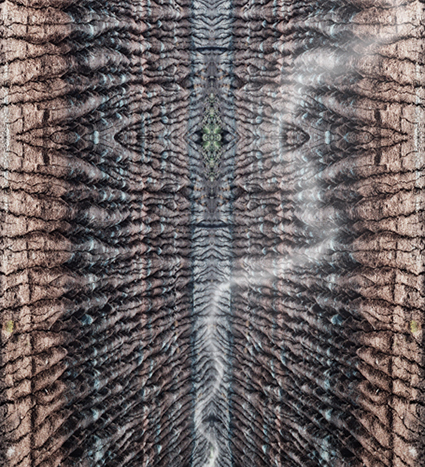

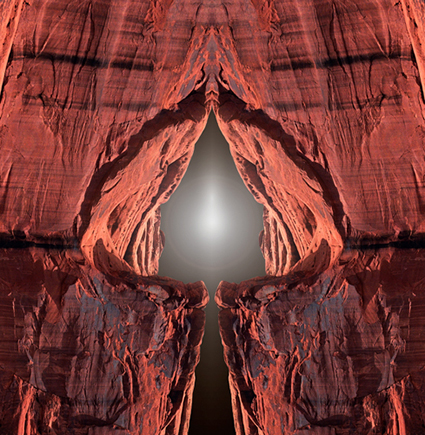

This is a selection of the images that started my series Revelation over twenty years ago. I had been planning on making related images in the arctic and antarctic for more than ten years. The series Revelation was on my mind when I first went to Antarctica in 2005; I started shooting deliberately for it on a return voyage in 2007; material slowly accumulated in subsequent voyages in 2009, 2011, 2013, and 2015; and then in 2016 it all came together. Part of the reason this work waited so long is that there was other work to do, including the completion of other related bodies of work including Inhalation and Exhalation. Doing that work influenced this work.

The images I recently released (arctic and antarctic Revelations) have a different quality as a result of waiting. they would have been different if I finished them earlier. In part, this comes from sleeping on it; the subconscious does a lot of work. In part, this is is the result of a significant amount of conscious thought; studying craft and composition were only the beginnings, digging into my thoughts and feelings about the subject and the approach were the real keys; related reading and viewing supported it. In part, this is the result of my inner state now; contrary to what some have suggested, I’ve found this isn’t something to overcome no matter what the current conditions but rather something to be nurtured and cultivated. While one needs to guard agains procrastination, one also needs to guard against rushing through content and not developing the necessary depth to fully engage it, fostering an intimate relationship with it. Doing the work develops depth. And, the work doesn’t just happen behind the lens or in front of the computer.

So when should you make work? This is a question that is best approached with awareness and deep contemplation. Though there are repeatable patterns and common tendencies, there is no one definitive answer to this question for all artists and all situations. I’ve found some work gets produced very quickly, sometimes a whole series is made in one shoot, and some work gets produced very slowly, over decades. Ultimately, I think you have to go with your gut. That doesn’t rule out the possibility and potential benefits of a great deal of research and forethought before you do. The two working in concert together often yield the most powerful combination. However, the single most important ingredient is, not mere spontaneity, which can be short lived, but an effervescence of spirit, and it’s particularly important to pay attention to this quality if it can be sustained over longer periods of time. One needs to be alive to the work to make it a living thing.

In the era of social networks, there is a tremendous pressure to release work quickly and to keep releasing work on a regular basis. This can create a pace that is unsustainable for most creatives, at least when it comes to releasing work with real depth. Good fully developed work takes time … because developing a relationship with your work and your self takes time, much like creating deeper relationships with people take time. Savor it.

At the same time, the unfinished work we make along the way has it’s own value, a very different value, and it can be fascinating to watch how we get to our final destinations. It’s important to know the difference and make the distinction between fully developed images and unfinished images, between work and play, both when we are producing our own images and enjoying others.

View new images in my series Revelation here.

View more images in the series Revelation here.

View the 360 degree interactive exhibit here.

View related Studies here.