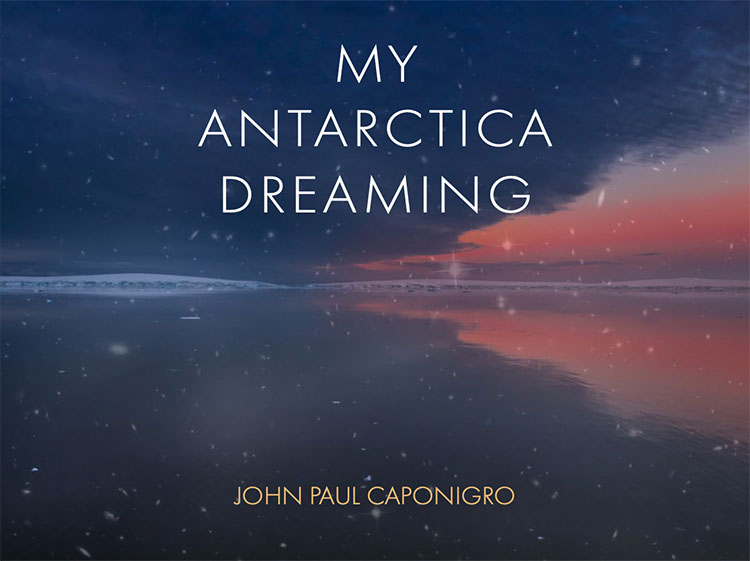

Do you remember your dreams?

If so, are you actively working with them?

Benefits

Throughout history, countless cultures have developed practices to cultivate their dreams and help people increase awareness, connect and clarify thoughts and feelings, recognize opportunities and issues, solve problems, optimize performance, and many other things. Never mind predicting the future, though that can happen too. As an artist, dreams help me imagine images, both realistic and surreal. As a writer, dreams help me write – letters, technical articles, aesthetic statements, nonfiction, fiction, and poetry. As a musician, dreams help me imagine new melodies, rhythms, and even sounds. Still, the biggest reason to remember your dreams is they’re fascinating. Dreams feel more real and are usually more entertaining, emotional, and insightful than movies or virtual reality.

Dreaming

All people (and many animals) dream. Scientists haven’t figured out all the reasons why dreams are so important for our mental and physical health. But they know we spend just under 10% of our lives dreaming. (That’s approximately 750 hours a year.) On average, we dream 2 hours a night in REM bursts lasting 10 minutes early in the night and gradually extending to as long as an hour.

Remembering

It’s common not to remember dreams. But there are many things you can do to improve your recall. The number one thing I’ve done to boost my recall is write down my dreams, not just first thing when I wake up, not just in the morning, but also when I wake up in the middle of the night. I do this using Notes on my iPhone; it’s always with me. During the pandemic, I’ve been more consistent than ever, and over 80% of the time I remember at least one dream. I found that when I traveled, I often let my routine slip, and my recall went down. When I reestablished this daily ritual, my recall went back up. Extending my dream practices from notation to journalling reflections and creating things in response to them has made dreams and my life much richer. I wish this for you too.

Resources

Many books have been written on dreams. I offer the following list of resources as a way to reinvigorate the journey you started long ago. These resources are not the classic academic books of great historians, anthropologists, scientists, and psychologists. I’ve chosen them because as well as being grounded in this long tradition, they’re also approachable and practical.

Sweet dreams!

Unlock The Secrets Of Your Dreams – Stephen Aizenstat – Free eBook

Read More