Join Me For My Free Artist Talk Online Aug 15 @ 08:30 PM

.

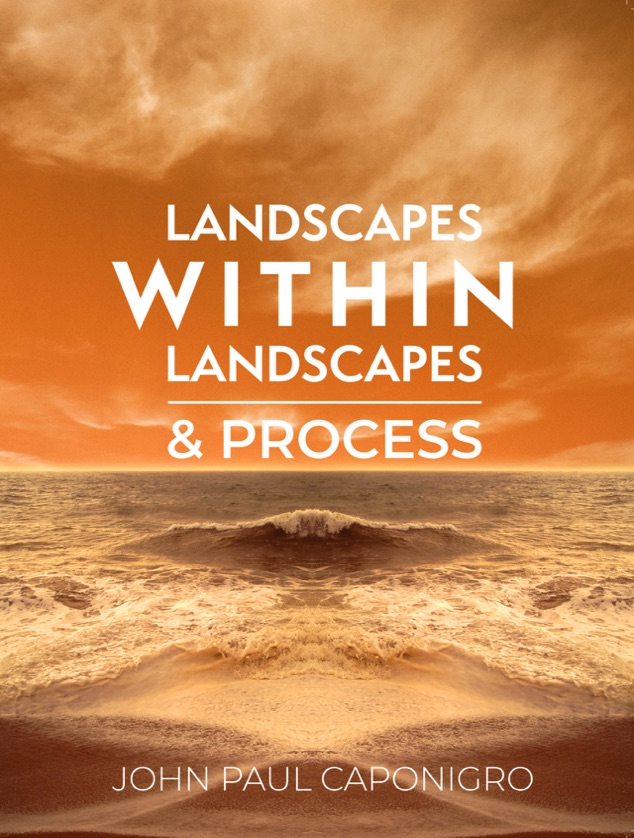

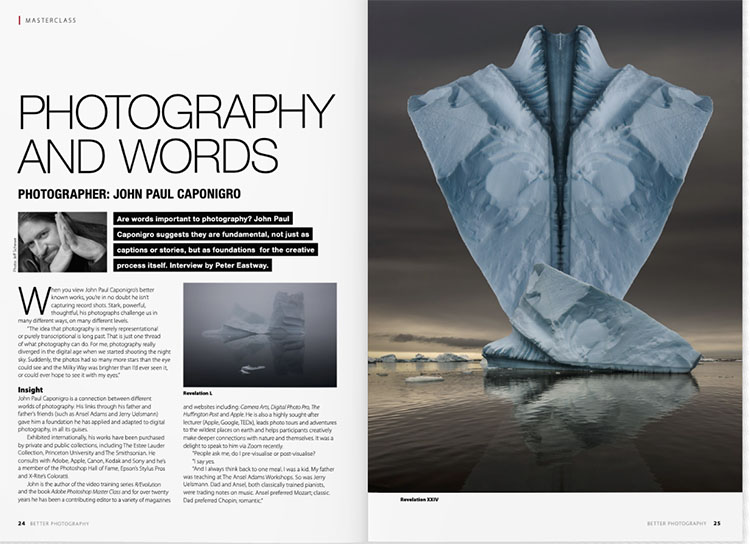

Enjoy an evening of pure inspiration as artist/photographer/writer John Paul Caponigro illuminates his creative process – not just where and how, but also why.

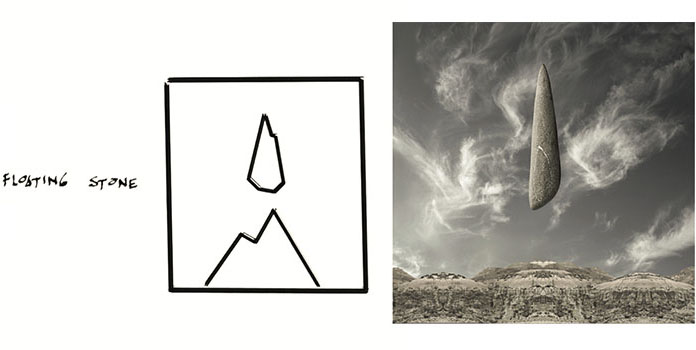

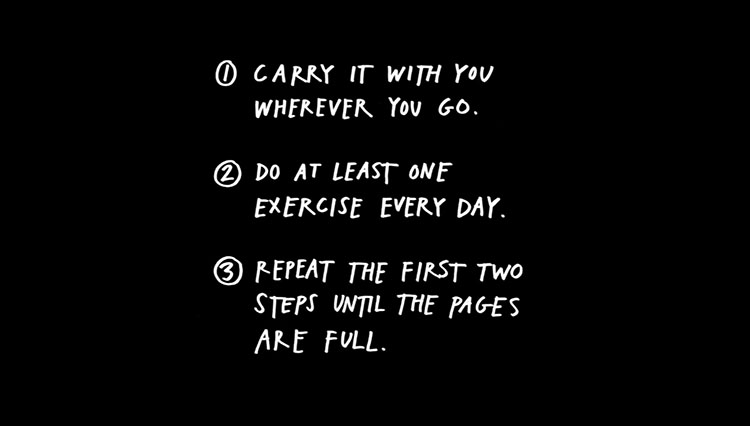

John Paul will show how he creates synergy between the diverse disciplines of drawing, photography, and writing, detailing how process influences perception – that ways of seeing lead to ways of being.

He’ll share sublime moments in locations around the world, circling behind an Icelandic waterfall, floating through an Antarctic iceberg graveyard, walking in the sky on a Bolivian salt flat, and flying like a bird over the Namibian coral dunes.

Finally, he’ll offer proof of how images of nature improve health. Like he does, you may conclude that we are not apart from nature but a part of Nature.

We’ll finish with a lively Q&A session.

Reserve your space for this special event now – space is limited.

About John Paul Caponigro

A form of environmental art in virtual space, John Paul Caponigro’s works are about the nature of perception and the perception of nature.

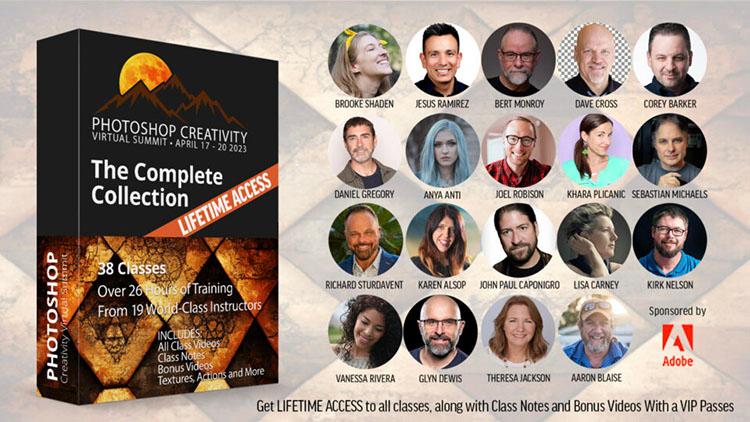

Exhibited internationally, his works have been purchased by private and public collections, including The Smithsonian, Princeton University, and The Estee Lauder Collection.

John Paul is a pioneer among visual artists working with digital media. He consults with the corporations that build the tools he uses, including Adobe, Apple, Canon, Kodak, and Sony. A member of the Photoshop Hall of Fame, Epson’s Stylus Pros, and X-Rite’s Coloratti, his images have been published widely in periodicals and books, including Art News and The Ansel Adams Guide.

Author of the video training series R/Evolution and the book Adobe Photoshop Master Class, for over twenty years, he has been a contributing editor to a variety of magazines and websites, including Camera Arts, Digital Photo Pro, The Huffington Post, and Apple. His creative nonfiction and poetry have been published in over 75 literary journals, in 17 countries, on 5 continents.

A highly sought-after speaker (Apple, Microsoft, MIT), teaching thousands in workshops and tens of thousands in lectures, he leads unique adventures in the wildest places on earth to help participants creatively make deeper connections with nature and themselves. Get a taste of what he does in his Google and TEDx talks.

Learn more – visit www.johnpaulcaponigro.art.