7 Simple Steps To Good Color Management

Color management is rocket science. But you don’t have to be a rocket scientist to drive the rocket. Instead, be an astronaut. With a few simple steps you can achieve consistent, high-quality color with your images every time.

These are the seven simple steps to good color management.

1 – Make Profiled Conversions

Assign an ICC profile to all image files either during Raw conversion or scanning. Use appropriate profiles to make conversions into other color spaces with derivative files only. Minimize the number of conversions made.

You won’t be doing this that often, once you standardize your workflow (creating all files in one color space)

2 – Use Hardware To Calibrate Your Monitor

Once a month, use a colorimeter to build an ICC profile for your monitor. Minimize the influence of other light sources during characterization. Use the colorimeter’s software to help you set monitor brightness between 90 and 100 and choose White Point D65 and Gamma 2.2. Check the results with know target images afterward.

Do this roughly once a month.

3 – Set Better Photoshop Color Settings

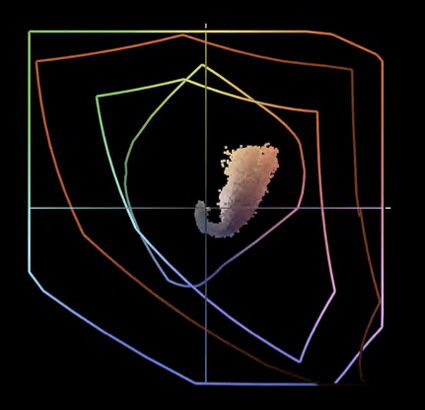

In Photoshop’s Color Settings (in the Edit Menu) Set Color Management Policies to Preserve Embedded Profiles and Ask When Opening / Pasting. And, choose a wide gamut device neutral editing space. Start with North American Prepress Defaults and then change RGB to ProPhoto RGB.

Do this once … and check it whenever Photoshop is updated.

4 – Profile Your Paper

Using a high-quality device make an ICC profile of your ink and paper combination. Or, have someone make a profile for you. Then make your prints with your custom profile. You’ll need different profiles for different papers. Consider profiles you download from websites suspect, sometimes ok but rarely great. (Skip this step if you’re printing on Epson paper with Epson printers. Their profiles are excellent.)

Do this once. Do it again when you change your paper type or printer ink.

5 – Softproof Before You Proof

Simulate the appearance of a print before printing. Go to View : Proof Setup : Custom and choose the profile you intend to print with. Check Simulate Paper Color and choose a rendering intent of either Perceptual or Relative Colorimetric. Make output-specific adjustments before printing. Use these adjustments only when printing these media.

Do this before you print individual image, but not multiples of the same image.

6 – Check The Correct Boxes In Your Printer Driver

Use Photoshop / Lightroom or your printer driver to manage color – not both. In general, favor using Photoshop/Lightroom as this is the most versatile allowing you to use custom output profiles.

Do this every time you print. Save custom settings so you can check multiple boxes with one click.

7 – Control Your Viewing Environment

Edit and evaluate your images in neutral surroundings. Minimize the effect of extraneous light sources, such as glare on monitors or backlighting. Evaluate proofs and prints in appropriate lighting.

Do this once.

There’s much more that can be said about each of these topics – but, not much more to do. Take these steps and you’ll be well on your way to achieving consistent, high-quality results with your images.

Read more on Color Management here.

Learn more in my digital photography and digital printing workshops.